Support for Native American Infants, Toddlers and their Families in California

Brief • Aug 23, 2023

Brief • Aug 23, 2023

About this Project

This brief is the result of a research project on issues facing the Native American community in California, and ways for community-based organizations to partner with Indigenous communities to best support them. The sources for this brief include a literature review and stakeholder interviews with First 5s and others with subject matter expertise. The brief highlights key learnings from this research, and provides a set of conclusions for First 5s and state and community leaders to consider as they work to be more inclusive and responsive to Native American families.

Table of Contents

More than 346,000 Native American children live in California.

Cultural strengths and cultural connection may protect Native American children from adversity.

Acknowledgements

This brief was developed by the First 5 Center for Children’s Policy. The First 5 Center staff reside throughout the territory currently known as California. Interviews, background research, and authorship of this paper were conducted by Leah Rooney (residing in the ancestral home of the Miwok and Patwin). Research supervision and editing support were provided by Sarah Crow (residing in the ancestral home of the Ohlone, Miwok, Muwekma and confederated villages of Lisjan) and Jaren Gaither (residing in the ancestral home of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, Chumash, and Gabrielino/Tongva Nation). Editing and communications support was provided by Tiana Cameron (residing in the ancestral home of the Miwok and confederated villages of Lisjan) and Melanie Flood (residing in the ancestral home of the confederated tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and Nisenan). We would like to thank Danielle Anderson-Reed, Mary Ann Hansen, and Ashley Villagomes from First 5 Humboldt, Sara Brown and Kim Goll from First 5 Orange, Mary Ann Bundang and Jennifer Covin from Health Quality Partners, Julie Gallelo from First 5 Sacramento, Nicole Hinton from First 5 Modoc, Misty Knight from Hoopa Valley Tribal Education, Karen Pautz from First 5 Siskiyou, and Hunter Watson from First 5 San Diego for their valuable input, feedback, and recommendations. This research was supported by Tipping Point Community and the Pritzker Children’s Initiative.

California is home to over 346,000 Native American children, one of the largest populations of Indigenous children in the U.S. These children live in all regions of the state and belong to many diverse cultures and communities. Numerous health and social disparities persist in Native American populations, which are evidence of generations of genocide, systemic racism, and trauma.

Nevertheless, Native American communities continue to thrive, and certain cultural strengths may protect Native American children from adversity. To effectively and equitably serve the youngest Native American children and their families in California, early childhood policies and programs must be responsive to their communities’ unique needs, experiences, and strengths.

About This Project

This brief is the result of a research project on issues facing the Native American community in California, and ways for community-based organizations to partner with Indigenous communities to best support them. The sources for this brief include a literature review and stakeholder interviews with First 5s and others with subject matter expertise. The brief highlights key learnings from this research, and provides a set of conclusions for First 5s and state and community leaders to consider as they work to be more inclusive and responsive to Native American families.

The First 5 Center acknowledges that the literature reviewed and cited here is saturated with studies about Native American population disparities and deficits, and few about strengths and resiliencies.1 In addition, Western, deficit-oriented indicators conflict with holistic strengths-based concepts of health and wellness in traditional Indigenous cultures, including for children’s development.2 Describing the population through a deficit lens perpetuates notions of racial inferiority and may be experienced as acts of continued colonization and assimilation.3 In an effort to draw attention to disparities and present an accurate account of the literature, this brief describes the challenges faced by Native American communities.

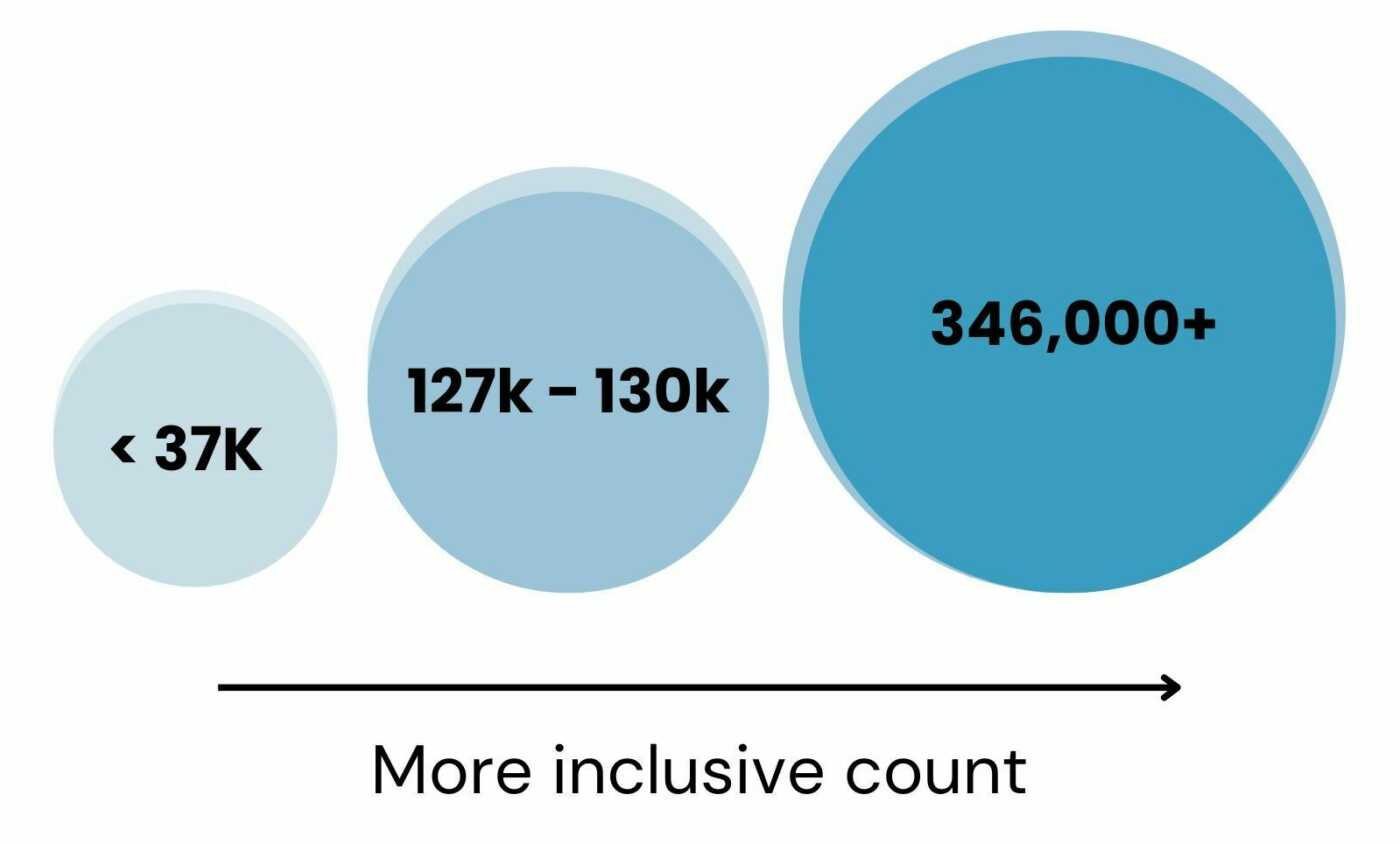

California is home to one of the largest populations of Native American children under 18 in the United States though population estimates vary greatly — from less than 37,000 to over 346,000 children.4

Estimates on the low end of this range rely on population data for only single-race, non-Hispanic Native American children.5 When including single-race Native American children who are also Hispanic, population estimates rise to between 126,970 and 130,174 children.6 These estimates rise even further — to between 211,606 and 346,346 children — when including all children who identify as Native American in any racial or ethnic combination.7

In a 2019 report, the California Department of Public Health found a similar change; Native American births in California increased 700% — from 1,765 to more than 13,000 births — when calculated using the most inclusive data definition.8

Subsets of data for single-race, non-Hispanic Native Americans exclude the vast majority of the total Native American population, yet these are the data sets most often available to researchers.9 Information about Native American populations is often further limited by racial misclassification, suppressed data, and the use of umbrella “other” categories for small population subgroups.10 Together, these practices can mask and misrepresent trends, as well as erase many Native Americans from the data story. Ultimately, it becomes easier to both overlook an already marginalized population and design ineffective, inequitable policies and programs.

For thousands of years prior to European colonization, the land we now call California was home to dozens of Indigenous populations with unique cultures and hundreds of languages. While many tribes, cultures, and languages were destroyed and lost, many survived or have been recovered.11

There are currently 110 federally recognized tribes that share geography with California, and several dozen more seeking recognition. Approximately 3% of Native Americans live on tribal lands — also known as reservations and Rancherias — while 90% live in cities and urban areas. Many of these Urban Indians are members of out-of-state tribes.12

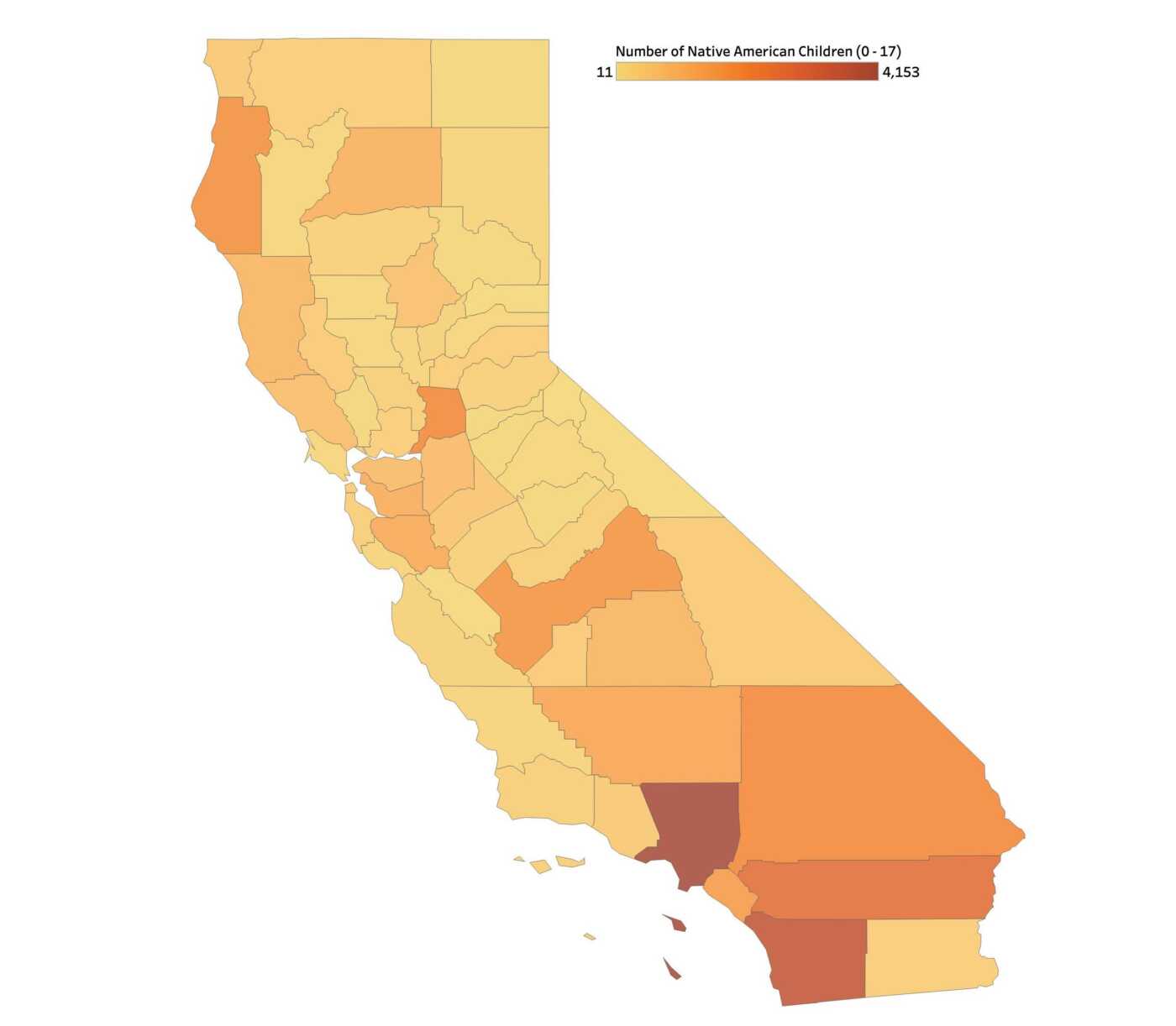

Today, Native American children live throughout the state, with the greatest number in several high-population counties such as Los Angeles, San Diego, and Riverside.13 However, Native American children make up a very small percentage of all the children in these counties. In contrast, while there are fewer children overall in several small-population counties such as Alpine, Inyo, Del Norte, and Humboldt, Native American children make up much larger shares of the children there.14

An abundance of research demonstrates many persistent health and social disparities in Native American populations. These include poorer health, lower life expectancy, more violence, very high suicide rates, disproportionate levels of poverty, and more severe maternal mortality compared to other groups.15

Research also shows higher rates of Native American infant mortality,16 early childhood poverty,17 childhood obesity and tooth decay,18 exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs),19 and over-representation in child welfare systems.20 In California, Native American infant mortality remains consistently higher than that of all children,21 and Native American children are placed in foster care at four times the rate of white children.22

Health and social disparities are not symptoms of individual behavior or biology, but of generations of genocide, racism, and trauma — including family separation and forced assimilation.23 Historical trauma in Native Americans has been linked to intergenerational substance abuse, depression, ineffective parenting, and emotional distress.24

Throughout California and the nation, Native American communities continue to thrive and certain cultural strengths may protect children from adversity.

Many Native American children are traditionally raised within extended family networks and in close intergenerational relationships through which traditions, practices, and values are passed down. Children are often parented not only by their biological parents, but by grandparents, aunts, uncles, and other biological and non-biological relatives.25

We know that a strong, positive, and stable relationship with just one adult can protect children from toxic stress and trauma.26 Meanwhile, Native American children are often surrounded by a whole network of adults committed to their physical, mental, and spiritual health.

A small body of research points to culture as a protective factor that promotes the health and well-being of Native American children. Stronger cultural connections — such as learning about one’s traditional culture, learning and using Native languages, and participating in spiritual practices — have been linked to positive outcomes and greater resilience in children.27 For example, Native American youth with strong cultural connections were less likely to have suicidal thoughts, and moms with strong connections to their Native American identities reported fewer developmental concerns in their toddlers.28

Given these outcomes, some early childhood leaders have sought to create and modify programs for Native American communities. Through interviews with First 5s, we identified playgroups and home visiting models that are designed to build on families’ strengths, recognize their cultural assets, and reinforce cultural connections.

Skuy’ Soo Hue-no-Woh Developmental Playgroup in Humboldt County

First 5 Humboldt’s developmental playgroup for Native families, Skuy’ Soo Hue-no-woh (“In a Good Way we Grow”), offers opportunities for caregivers of young Native American children to access developmental information and connect with other adults while children play and socialize. A fluent Yurok language speaker attends most of the playgroup sessions and speaks only in Yurok, which creates an immersive language experience for children and their caregivers.

The Native families playgroup is supported through First 5 Humboldt’s Playgroup Grant Program and offered in partnership with Two Feathers Native American Family Services, the Yurok Tribe Language program, and the McKinleyville Family Resource Center. First 5 Humboldt credited these respectful partnerships with local Native-led organizations with the playgroup’s success, specifically by building trust, lending credibility to First 5, and eliminating barriers for client families.

This is the first of First 5 Humboldt’s two playgroups specifically designed for local Native families. The program was created to provide these families with consistent community space to connect with each other. First 5 Humboldt staff explained, “Native families don’t always see themselves represented in community spaces [so the playgroup has been] framed as largely for and by Native families.”

Road to Resilience Program in Humboldt and Del Norte Counties

Road to Resilience29 in Humboldt and Del Norte Counties is a voluntary home visiting and case management program for new and expectant Native American mothers who are at risk of or currently experiencing substance abuse. Perinatal healthcare navigators provide various levels of personalized support to clients and their families. Family Spirit is one of two home visiting curricula utilized; while not implemented to fidelity, the curricula serve as guides to respond to clients needs:

Care navigators are members of local Indigenous populations, which helps to build trust with clients. Navigators receive cultural humility, trauma-informed, community health, and other basic and specialized training. They may provide families with physical resources and incentives, help schedule appointments, and sometimes attend court visits with clients. Client families may also receive locally-made cultural items, such as hand-woven baby rattles or a traditional baby basket, both of which help to reinforce cultural and community connections.

First 5 Humboldt partners with the United Indian Health Service (UIHS) to deliver Road to Resilience services to client families through the network of UIHS clinics in Humboldt and Del Norte counties. The Road to Resilience Program is funded by a Road to Resilience grant from the Office of Child Abuse Prevention (OCAP) which prioritized applicants affiliated with tribes, populations overrepresented in child welfare systems, and under-resourced geographic regions.30

First 5 Humboldt was invited by local Indigenous leaders to apply for the OCAP grant, which is indicative of the trusting and authentic relationships that First 5 has established with local Indigenous communities in recent years. These developed through First 5 staff’s professional and personal connections, and with a commitment to listening, learning, and knowing when it is and is not appropriate to offer support. First 5 Humboldt recognizes that while it has valuable early childhood expertise and resources to offer, it is essential not to impose solutions to perceived problems, but to instead respond to stated needs at the request of local Indigenous communities and leaders.

Strong Starts for Strong Families in Modoc County

In 2022, First 5 Modoc awarded a grant to Strong Families Health Center, an inter-tribal health center and service provider based in Alturas, for a pilot home visiting program called Strong Starts for Strong Families. The program serves tribal members of Cedarville Rancheria and other local families. Program staff utilize the evidence-based Nurturing Parenting home visiting curriculum, but with modifications to ensure lessons are culturally sensitive and appropriate. The pilot program also includes developmental playgroups for all families, tribal or non-tribal.

First 5 Modoc views its partnership with Strong Families Health Center as an example to other county systems of how to make space for and more equitably serve tribal families who have for too long been isolated, under-resourced, and under-served. This partnership is part of First 5 Modoc’s broader effort to connect with and support local tribal families through prevention-focused programming and extensive community outreach.

Other home visiting programs for Native American families in California

In addition to First 5s’ models, Native American families in California may also receive home visiting through a network of programs delivered by counties, community-based organizations, and tribal-led organizations. In 2021, tribal-led organizations delivered evidence-based home visiting programs in at least eight California counties.31

Two federally-funded home visiting programs specifically focus on Native American families:

Although not designed specifically for Native American families, Native American families may also receive home visiting services through:

A note on evidence-based home visiting:

Evidence-based home visiting models are often considered the gold standard, but they can be costly and difficult to implement to fidelity. Further, only one of the 23 programs that meet federal standards of effectiveness has been rigorously evaluated in tribal populations. This program, Family Spirit, treats culture as a protective factor and the curriculum can be adapted to local communities’ practices and traditions.40 There are currently seven programs offering Family Spirit in California.41 Forty-two counties are currently participating in CalWORKs HVP.

Research suggests that using evidence-based curricula for Native American populations may not be effective nor appropriate without cultural adaptations.42 Evidence-informed or locally-evaluated home visiting models, however, can be tailored to local communities’ unique needs and practices.

More than 346,000 racially and culturally diverse Native American children live throughout California. These children and their families belong to diverse communities with unique cultural strengths that can be promoted through family-centered, culturally-responsive early childhood systems and services.

To more equitably and effectively support Native American families, early childhood service providers, funders, and policymakers should:

Appendix A. Estimated population of Native American children ages 0-17 in California, by racial/ethnic category.

Racial/Ethnic Category | N | Source |

|---|---|---|

Single race, non-Hispanic | 23,714 | The Children’s Partnership, 2022 |

30,371 | Kids Count, 2022 | |

36,400 | KidsData, 2021 | |

Single race, Hispanic or non-Hispanic | 126,970 | U.S. Census Bureau, 2023 |

130,174 | The Children’s Partnership, 2022 | |

Single or multiracial, Hispanic or non-Hispanic | 211,606 | The Children’s Partnership, 2022 |

346,346 | U.S. Census Bureau, 2023 |

Appendix B. Estimated population of single-race, non-Hispanic Native American Children Ages 0-17 in California, by county: 2021

Location | N | % of all children |

|---|---|---|

California | 36,400 | 0.4 |

Alameda County | 1,057 | 0.3 |

Alpine County | 49 | 30.1 |

Amador County | 85 | 1.5 |

Butte County | 622 | 1.4 |

Calaveras County | 74 | 1.1 |

Colusa County | 99 | 1.7 |

Contra Costa County | 700 | 0.3 |

Del Norte County | 437 | 8.0 |

El Dorado County | 257 | 0.7 |

Fresno County | 1,636 | 0.6 |

Glenn County | 105 | 1.4 |

Humboldt County | 1,738 | 6.3 |

Imperial County | 357 | 0.7 |

Inyo County | 388 | 10.5 |

Kern County | 1,237 | 0.5 |

Kings County | 393 | 0.8 |

Lake County | 404 | 3.0 |

Lassen County | 144 | 2.7 |

Los Angeles County | 4,153 | 0.2 |

Madera County | 316 | 0.8 |

Marin County | 109 | 0.2 |

Mariposa County | 65 | 2.4 |

Mendocino County | 846 | 4.6 |

Merced County | 238 | 0.3 |

Modoc County | 68 | 3.9 |

Mono County | 28 | 1.0 |

Monterey County | 228 | 0.2 |

Napa County | 64 | 0.2 |

Nevada County | 141 | 0.9 |

Orange County | 1,491 | 0.2 |

Placer County | 347 | 0.5 |

Plumas County | 91 | 2.9 |

Riverside County | 2,651 | 0.5 |

Sacramento County | 1,893 | 0.5 |

San Benito County | 38 | 0.3 |

San Bernardino County | 1,892 | 0.3 |

San Diego County | 3,528 | 0.4 |

San Francisco County | 328 | 0.2 |

San Joaquin County | 717 | 0.4 |

San Luis Obispo County | 197 | 0.4 |

San Mateo County | 296 | 0.2 |

Santa Barbara County | 279 | 0.3 |

Santa Clara County | 1,147 | 0.3 |

Santa Cruz County | 163 | 0.3 |

Shasta County | 988 | 2.6 |

Sierra County | 11 | 2.5 |

Siskiyou County | 359 | 4.3 |

Solano County | 330 | 0.3 |

Sonoma County | 688 | 0.8 |

Stanislaus County | 477 | 0.3 |

Sutter County | 194 | 0.8 |

Tehama County | 272 | 1.9 |

Trinity County | 102 | 4.5 |

Tulare County | 857 | 0.6 |

Tuolumne County | 106 | 1.3 |

Ventura County | 432 | 0.2 |

Yolo County | 275 | 0.5 |

Yuba County | 213 | 1.0 |

Data Note: These population estimates for single-race, non-Hispanic Native American children do not include children who identify as multiracial and/or Hispanic.

Data Source: California Department of Finance, Population Estimates and Projections; U.S. Census Bureau, Population and Housing Unit Estimates (Aug. 2021), as cited on Kidsdata.org, Child population by race/ethnicity in California: 2021. https://www.kidsdata.org/topic...