The Role of First 5s in Home Visiting: Innovations, Challenges, and Opportunities in California

Report • Jul 6, 2022

Report • Jul 6, 2022

Summary

Because of their long-standing commitment to home visiting, First 5s hold a wealth of knowledge about the current landscape of home visiting across the state. Highlighting both innovation and challenges, this paper explores the ways in which First 5s play a role in home visiting in California. Click here to read our blog post about the paper and research process.

Table of Contents

The First 5 Center for Children’s Policy initiated a qualitative research project involving a series of interviews with 54 First 5s across the state.5 The following themes emerged from the narrative interviews:

» History of home visiting investments and successes

» Shifts to equity-driven practices

» Factors contributing to First 5s’ transition to systems-level focus

This paper presents the findings of these interviews and their implications for home visiting in California.

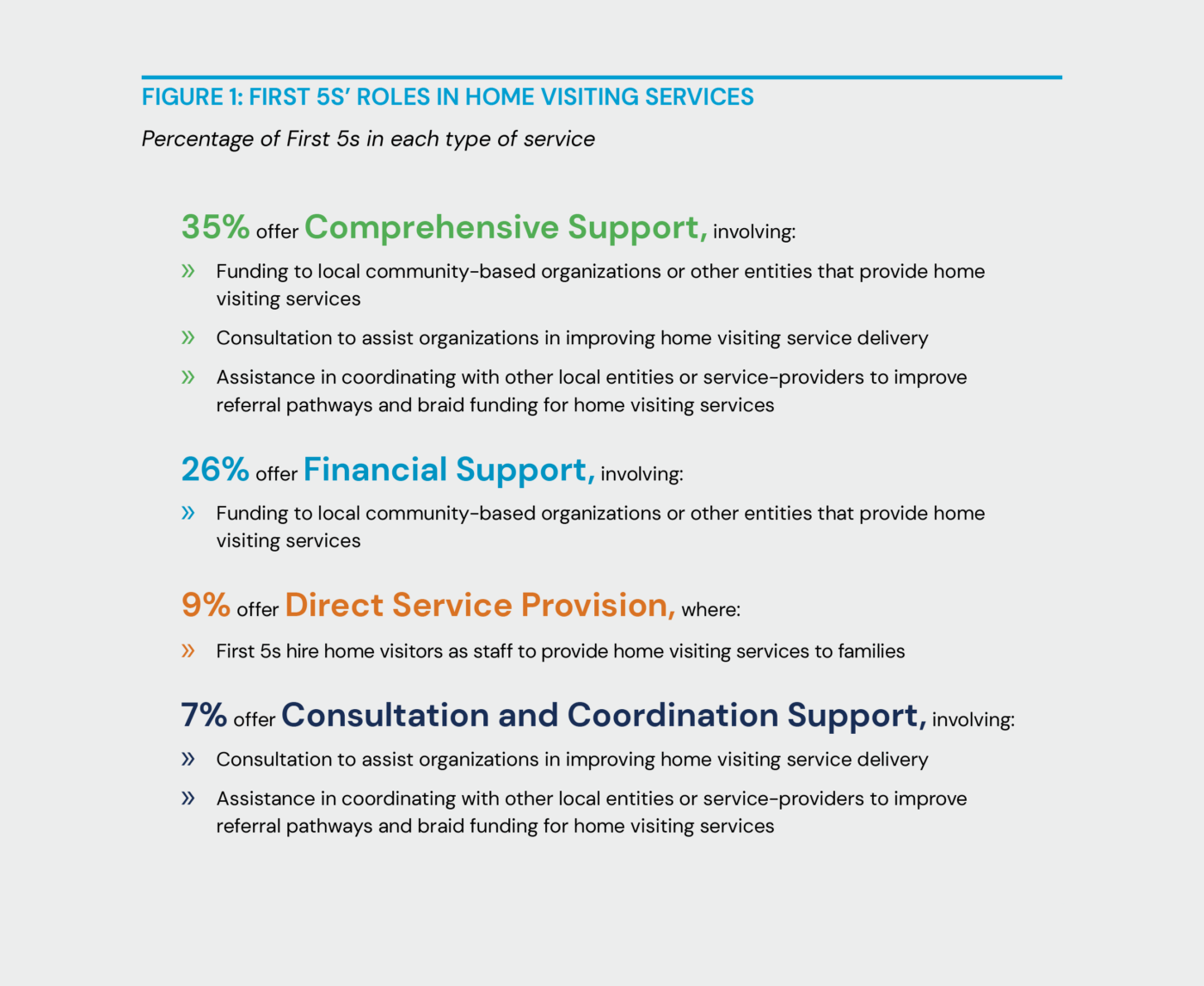

42 out of 54 (or 78%) of First 5s interviewed indicated active involvement in home visiting. First 5s delineated their involvement in home visiting services and systems in four main ways, described in Figure 1 below.6

The First 5 Center for Children’s Policy initiated a qualitative research project involving a series of interviews with 54 First 5s across the state.5 The following themes emerged from the narrative interviews:

» History of home visiting investments and successes

» Shifts to equity-driven practices

» Factors contributing to First 5s’ transition to systems-level focus

This paper presents the findings of these interviews and their implications for home visiting in California.

1. FIRST 5S HAVE SIGNIFICANT AND LONG-TERM INVOLVEMENT IN HOME VISITING SERVICES AND SYSTEMS.

42 out of 54 (or 78%) of First 5s interviewed indicated active involvement in home visiting. First 5s delineated their involvement in home visiting services and systems in four main ways, described in Figure 1 below.6

About half of interviewees indicated that their First 5 had invested funding and/or other resources in home visiting for 10 years or more. First 5s with over 10 years of involvement in home visiting noted that the consistent presence in their communities facilitated relationship-building with both families and community partners, like local universities, other community-based organizations (CBOs), libraries, and Family Resource Centers (FRCs). Several respondents linked the strength of these relationships to a more robust knowledge of the needs of their local communities, informing strategies and action to better meet those needs.

Indeed, home visiting’s capacity to facilitate relationship-building in multiple contexts is one of the key reasons underlying First 5s’ long-standing involvement. Many interviewees highlighted how home visitors build strong, trusting relationships with families with young children. The combination of social support and resources (such as child development guidance, referrals to health and social services, and sometimes concrete supports like diapers, wipes, and books) provided by home visitors create an environment that reduces families’ stress and enhances caregivers’ relationships with their children. Several interviewees also highlighted the flexibility of services as another major factor contributing to home visiting’s enduring role among First 5s’ other family resiliency initiatives and programs. Home visiting programs are able to “meet families where they’re at,” adapting to families’ needs and schedules. This flexibility further builds trust between the home visitor and the family, facilitating the visitors’ understanding of the family’s needs, and enabling them to determine and procure the supports to best address those needs. This ultimately results in a range of improved outcomes enhancing the well-being of families and young children–individuals who are often impacted by poverty, structural racism, and other social inequities.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the ability of home visiting to substantially influence outcomes for families and young children is a major reason why First 5s have had such a consistent interest in home visiting. Many of the early-adopter First 5s noted how they initially implemented home visiting because of its effectiveness in reducing child maltreatment. Over the years, however, many First 5s have also recognized how home visiting can also positively improve numerous other outcomes related, but not limited to: prenatal health, postpartum depression, children’s physical health (including immunizations, Well-Child Visits, and dental visits), and children’s school readiness.

First 5s dedicate significant portions of their budgets towards home visiting because of its demonstrated effectiveness in improving child and family outcomes across multiple domains.

Nineteen percent of First 5s estimate dedicating a third or more of their budgets, an additional 29% estimate allocating between 15% and 30% of their budgets, and 23% estimate allocating between 1% and 15% of their budgets.

2. FIRST 5S ADAPT PROGRAMS AND APPROACHES TO MEET CHANGING NEEDS

First 5s have the ability to flexibly meet community need, more so than other public entities at the county level that are bound by additional state mandates. Over the 20 years of First 5s’ existence, they have adjusted funding and programming as needs change and lessons are learned. First 5 Imperial County, for example, described how their home visiting efforts have evolved in significant ways to meet community needs. Initially, First 5 Imperial started with light-touch home visiting programs, then shifted to providing more intensive services, like case management, nurse visits, and specific supports to children with hearing issues. For the last 11 years, it has funded Project NENEs, which is a 30-week Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) program that supports families with children ages 3 to 5. A recent review of early childhood data reflected low breastfeeding rates in the county, so First 5 Imperial is working to add home visiting services that focus on infants and toddlers.

A major adaptation voiced by many First 5s included pandemic-related pivots. Home visiting programs administered by public health departments suffered significant setbacks as many public health nurses were temporarily reassigned to COVID response teams.

At the same time, many First 5s recognized the growing needs of families with young children in their communities, particularly families who were economically insecure. Several interviewees described flexibility and responsiveness of their local First 5s to COVID, adapting to and meeting the changing needs of families by swiftly transitioning to virtual home visiting approaches. Most First 5s described how their funded programs began supporting families with basic needs, distributing food, diapers, and formula.

3. FIRST 5S ARE SHIFTING TOWARDS EQUITY-DRIVEN APPROACHES.

In recent years and particularly galvanized by the racial reckoning of 2020, some First 5s across the state have made a more explicit and focused commitment to Race, Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion (REDI). Interviewees identified a range of activities and policies that reflect this increased commitment. First 5 Butte County, for instance, intentionally pursued opportunities to support the county’s Hmong population through culturally-relevant home visiting and other family strengthening services by partnering with the Hmong Cultural Center. First 5 Sutter County, for example, noted the importance of home visiting staff who reflect the racial/ethnic make-up of the community and are sensitive to any language and cultural barriers. Some First 5s are reconsidering their grant-application processes to facilitate equitable opportunities for local community-based organizations that administer home visiting. First 5 Humboldt County sends Requests for Applications (RFAs) to organizations that aim to impact structural racism through their work, and offers additional assistance in completing applications if needed. In grant applications for home visiting and other local programs, First 5 Merced County has taken intentional steps to remove as many technical components in their grant processes to eliminate bias towards academic or higher educational language.

Another major REDI-focus area in which First 5s have grown in recent years includes community and family engagement efforts, which influence home visiting approaches

and investments. While many home visiting program models and grantee requirements involve some degree of family and caregiver feedback (sometimes through surveys or focus groups), several First 5s indicated a desire to strengthen their community engagement efforts. Several First 5s, such as First 5 Alameda, Placer, Nevada, Contra Costa, and Humboldt Counties, prioritize parent and community engagement by including parent representatives in collaboratives, Community Advisory Councils, or even on the Commission itself. By intentionally seeking out family voices in this way, First 5s can improve the effectiveness of their programs, including their home visiting programs.

First 5s also acknowledged the need to continue improving processes for engaging parents and communities in decision making. First 5s noted that more direct community engagement is needed across systems and programs.

While many First 5s are stepping back to take a deep look at equity practices through funding, service provision, and practices, there are systems-level barriers at state and local levels, which hinder efforts to improve equity practices in home visiting. Hiring culturally and linguistically diverse staff is a challenge for many First 5s, especially in more rural settings. Due to these hiring challenges, some counties are not able to provide adequate multicultural or multilingual services. The issue of hiring diverse staff is even more present in areas serving tribal or migrant populations. Because these groups may be less likely to trust providers who do not share language or cultural backgrounds, First 5s and their funded home visiting programs struggle to provide culturally-relevant services to families in these areas.

As part of equity considerations, some First 5s are actively engaged in discussions about the pros and cons of targeted versus universal home visiting approaches. In some more diverse or densely populated areas, targeted home visiting and programming allows counties to serve high-risk populations or specifically underserved communities. Some consider this targeted approach to be the more equitable approach to home visiting. However, in areas where populations are less diverse, or in areas where programming for underserved populations is robust, some First 5s endorsed a universal approach to home visiting referrals and recruitment to reach families not traditionally seen as high-need for intervention. In these instances, interviewees felt that the universal approach was more equitable. This variation highlights not only distinct community needs, but perhaps also different definitions of equity.

EVIDENCE-BASED VERSUS EVIDENCE-INFORMED HOME VISITING MODELS

Another salient topic echoed across several interviews is that of evidence-based versus evidence-informed or “home grown” models. Of those counties that offer home visiting programs, most offer at least one evidence-based model, such as Nurse Family Partnership

(NFP), Parents as Teachers (PAT), or Healthy Families America (HFA). Many First 5s described making significant investments to gain accreditation and implement these evidence-based models, in some cases because of the models’ researched impact on improving child and family outcomes, which they believed would increase stakeholder buy-in. Other counties appreciated the implementation and evaluation features accompanying some evidence-based models. Other First 5s noted their interest in supporting evidence-informed models to better serve a community through tailored, culturally-relevant programming that may deviate from existing evidence-based curricula. First 5 Butte County, for example, funds Tu Tus Menyuam, which is a Hmong-language home visiting and parent support program operated by the Hmong Cultural Center. Some First 5s expressed frustration about the threshold requirements of public funds requiring the use of evidence-based programs. A common concern voiced by many respondents was the high cost associated with implementing evidence-based home visiting models, and doing so with fidelity. Moreover, they expressed concerns that evidence-based models may not be as responsive as home-grown models to unique populations’ needs.

4. FIRST 5S ARE ADOPTING A SYSTEMS-LEVEL FOCUS AS THE LANDSCAPE OF HOME VISITING FUNDING CHANGES.

As home visiting funding has changed over the last 20 years, the level of First 5 involvement in home visiting for much of the state has shifted from providing direct service or large financial support to driving broader systems-level approaches. First 5s cited varying factors contributing to these shifts, mainly related to funding constraints and new home visiting opportunities. As Proposition 10 revenues decrease, counties must leverage funding to maximize impact.7 For example, many First 5s are leading efforts to integrate home visiting as a part of a larger system of care for families, including through Help Me Grow systems and Family Resource Centers. These approaches allow counties to offer wraparound services for families, including early literacy, WIC, and other assistance programs.

FAMILY RESOURCE CENTERS

While Family Resource Centers (FRCs) offer out-of-home family strengthening programs, many of the services provided by traditional home visitors are still offered in these alternative settings, and are another focus area of First 5s in their efforts to support families. FRCs are often located in at-risk or high-need communities and while some counties invest in both home visiting and FRCs, a subset of counties shifted focus to exclusively funding FRCs. Across several interviews, First 5s described how FRCs typically serve as centralized community hubs where families can access a wide variety of services and resources. These might include basic needs assistance, parenting education, individual and family counseling, domestic violence support groups, housing support, as well as referrals to health care and other services, like home visiting. In a number of counties, FRCs also directly operate home visiting programs.

First 5s saw their role as direct service funder shift as new federal- and state-level funding streams have become available to fund home visiting:

In 2019, First 5 California released Home Visiting Coordination Grants, authorizing up to

$24 million over 5 years, for local, regional, and statewide coordination efforts toward sustainable, unified home visiting systems. So far, approximately $12 million has been invested on Home Visiting Coordination projects in counties to improve referral systems, strengthen coordination among providers and programs, improve the quality of programs to be more responsive to California’s diverse families, and more effectively braid and maximize funding sources at the local level.11 This grant has also provided essential resources for counties to conduct their own home visiting landscape reports, regardless of their current level of involvement in home visiting. In many cases, this funding opportunity allowed counties to better triage their resources, ensuring that resources were distributed to the organizations and communities most in need.

SMALL POPULATION COUNTY PERSPECTIVE

In California’s rural small population counties, there are significant infrastructure barriers that raise the costs of appropriately and effectively implementing home visiting programs. Families with young children are often not clustered in central, accessible areas. Communities may have limited internet and cellular service, as well as lower access to health care and other social services. For some counties, the nearest hospital or care facility might be in another state; for others, it’s hours away in another county. Transit is also a challenge for families who lack access to a car in small population counties where public transit is unavailable. Even if families do have access to transportation, the long distances to areas with services sometimes require families to travel for hours to access services.

First 5s have developed innovative coordination strategies to optimize home visiting efforts, increasing collaboration with county governments, community-based organizations, and other public agencies. About a third of respondents described successes in building relationships with partners to enhance home visiting for families and reduce duplication. First 5 Placer County, for example, works closely with the FRC network in their community to implement Parents as Teachers (PAT), an evidence-based home visiting model. First 5 Placer pays for and holds the accreditation for PAT. FRCs are then able to implement the PAT curriculum, reducing the costs for any individual FRC to offer the model.

A number of First 5s streamline processes to refer families to other services or resources, such as housing, social services, and health care. First 5 Merced County used the Home Visiting Coordination grant to develop strategies for improving successful referral follow-up by facilitating warm hand-offs, or introductions, between clients’ providers. First 5 Humboldt County recently made sizable investments in a community information exchange to develop a closed-loop referral system that is integrated with social service systems and electronic health records.

Defining “home visiting.” Across interviews with First 5s, there was a considerable difference in their descriptions of program goals and other features, raising questions about the definition of the term “home visiting.” This variability in home visiting definitions reflects the flexibility of services and programs to meet the specific needs of the families they serve. These varying definitions create challenges, however, when trying to communicate about the services and to evaluate trends and assess effectiveness of home visiting across the state.

The goal of services described by interviewees ranged from ameliorating effects of adverse childhood experiences, to child abuse prevention, medical intervention, or school readiness. Indeed, home visiting has demonstrated outcomes in many domains and can be implemented flexibly depending on a family’s need. Interviewees not only identified a range of goals associated with home visits, but also varied with respect to a number of factors relating to home visiting implementation. Some counties include low-intensity case management, or infrequent programming, within their definition of home visiting, while other areas only consider higher dosage programming as home visiting.

Clarification on the definition and goals of home visiting will not only aid in future policy and advocacy, it will also allow for clearer communication with families and communities.

Narrative interviews for this project revealed the shifting landscape of home visiting in California, which reflect First 5s’ successes in developing innovative home visiting approaches that are responsive to family and community needs. First 5s’ innovation in this space

cannot be understated, especially considering the tremendous societal changes that have necessitated shifts in the home visiting field. As some of the earliest adopters of home visiting programs and innovative experts deeply familiar with the needs of their local communities, First 5s are a source of invaluable information to help California meet this moment of change for family-serving systems. First 5s’ long-standing commitment and role at the county

level make them important coordination partners to county departments in the continued implementation of a wide range of home visiting and other programs that meet family needs.

This brief was developed by the First 5 Center for Children’s Policy. Interviews and background research for this paper were conducted by Rebecca Murillo (a student in the USF Masters in Urban and Public Affairs Program ‘22) and Katie Cannady (a student in the UC Berkeley Public Policy Program ‘22). Research supervision and editing support was provided by Alexandra Parma. It was authored by Sarah Crow and Kit Strong. Editing and communications support was provided by Melanie Flood and Caitlyn Schaap. The authors thank the many experts who were interviewed for this report:

Alethea Arguilez, Executive Director, First 5 San Diego County

Rita Baker, Program Coordinator, First 5 Yuba County

Anna Bauer, Executive Director, First 5 Butte County

Michelle Blake, Executive Director, First 5 Sutter County

Michelle Blakely, Deputy Director, First 5 San Mateo County

Amy Broadhurst, Executive Director, First 5 Alpine County

David Brody, Executive Director, First 5 Santa Cruz County

Diana Careaga, Director of Family Supports, First 5 Los Angeles County

Leticia Casillas Sanchez, Former Vice President of Programs, First 5 Orange County

Tim Clark, Executive Director, First 5 Lassen County

Rosie Contreras, Home Visiting Supervisor, First 5 San Benito County

Gina Daleiden, Executive Director, First 5 Yolo County

Sabrina Dean, Associate Manager, Programs, First 5 Placer County

Molly Desbaillets, Executive Director, First 5 Mono County

Maria Diaz-Ruiz, Home Visitor, First 5 San Benito County

Angie Dillon-Shore, Executive Director, First 5 Sonoma County

Thanh Do, Former Deputy Chief of Community Health & Wellness, First 5 Santa Clara County Melody Easton, Executive Director, First 5 Nevada County

Ruth Fernandez, Executive Director, First 5 Contra Costa County

Oscar Flores, Senior Programs Manager, First 5 Monterey County

Juanita Garcia, Projects Coordinator, First 5 San Diego County

Sarah Garcia, Executive Director, First 5 Tuolumne County

Kim Goll, Executive Director, First 5 Orange County

Fabiola Gonzalez, Executive Director, First 5 Fresno County

Tammi Graham, Executive Director, First 5 Riverside County

Michele Grupe, Executive Director, Cope Family Center; First 5 Napa County Commissioner Kathi Guerrero, Executive Director, First 5 El Dorado County

Alejandro Gutierrez-Chavez, Research & Evaluation Specialist, First 5 San Bernardino County

Mary Ann Hansen, Executive Director, First 5 Humboldt County

Samantha Hernandez, Quality County Program Officer, First 5 San Benito County

Nicole Hinton, Executive Director, First 5 Modoc County

Lenette Javier, Program & Evaluation Administrator, First 5 San Diego County

Serena Johnson, Executive Director, First 5 Inyo County

David Jones, Executive Director, First 5 Stanislaus County*

Carla Keener, Director of Programs, First 5 Alameda County

Suzi Kochems, Executive Director, First 5 Trinity County

Lisa Korb, Family Support Program Officer, First 5 Contra Costa County

Alejandra Labrado, Home Visiting and Parent Liaison Manager, First 5 Sacramento County Teri Lane, Executive Director, First 5 Calaveras County

Amira Long, Executive Director, First 5 Del Norte County

Nina Machado, Executive Director, First 5 Amador County

Roland Maier, Executive Director, First 5 Kern County

Colleen Masi, Parents As Teachers Home Visiting Program Manager, Cope Family Center Scott McGrath, Deputy Director of Systems & Impact, First 5 San Bernardino County Heidi Mendenhall, Executive Director, First 5 Tehama County

Michele Morrow-Eaton, Executive Director, First 5 Tulare County

Julie Murphy, Program and People Director, First 5 Napa County

Hannah Norman, Early Childhood Initiatives Director, First 5 Fresno County

Sarah O’Rourke, Former Program Manager, First 5 Orange County

Kelsey Pennington Bhatnagar, Director of Community Health & Wellness, First 5 Santa Clara County

Elizabeth Poole, Deputy Director, First 5 Shasta County

Petra Puls, Executive Director, First 5 Ventura County

Camilla Rand, Deputy Director, First 5 Contra Costa County

Clarissa Revelo, Program Officer, First 5 Kings County

Megan Richards, Deputy Director, First 5 Solano County

Carla Ritz, Executive Director, First 5 Lake County

Michelle Robertson, Deputy Director, First 5 Santa Barbara County

Julio Rodriguez, Executive Director, First 5 Imperial County

Alexandra Rounds, Home Visiting Coordinator, First 5 Mendocino County

Lani Schiff-Ross, Former Executive Director, First 5 San Joaquin County

Karen Scott, Executive Director, First 5 San Bernardino County

Erika Summers, Executive Director, First 5 Yuba County

Xochitl Villasenor, Program Manager, First 5 Madera County

Scott Waite, Executive Director, First 5 Merced County

Lisa Watson, Evaluation Consultant to First 5 Plumas and First 5 Sierra Counties, Social Entrepreneurs, Inc.

Nikki West, Executive Director, First 5 Mariposa County

Pat Wheatley, Former Executive Director, First 5 Santa Barbara County

Theresa Zighera, Interim Executive Director, First 5 San Francisco County

This research was supported by the Pritzker Children’s Initiative.

*David Jones passed away in May 2022. He made significant contributions to the First 5 network, and will be missed.